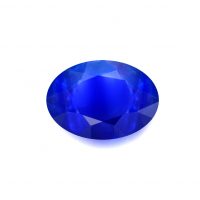

September’s birthstone, Sapphires are truly mesmerizing, with a rich history, potent symbolism, and popularity spanning over 2,500 years. Quintessentially beautiful, rare and wearable, Sapphires are among the most revered and valuable gemstones. Prized for their wonderful colors and brilliance, Madagascar can even rival Ceylon and Kashmir Sapphires. Once unearthing around half of the world’s Sapphires, Madagascar remains significant and esteemed, despite ever-decreasing availability. Long-vaulted from the famous Ilakaka (ee-lah-KAH-kah) Gem Deposit, one of the world’s largest Sapphire fields discovered in 1998, these gorgeous rosy and orchid Madagascan Pink Sapphires are increasingly scarce…

Beauty

Coupled with excellent brilliance and transparency, Madagascan Pink Sapphires beautifully display pinks to slightly purplish-pinks with a highly-desirable medium-light to medium saturation (strength of color) and tone (lightness or darkness of color).

Our Madagascan Pink Sapphires were optimally faceted in the legendary gemstone country of Thailand (Siam), home to some of the world’s best Corundum lapidaries. Each Sapphire was carefully orientated to maximize its colorful brilliance, maintaining an eye-clean clarity (the highest quality clarity grade for colored gemstones as determined by the world’s leading gemological laboratories), a high/mirror-like polish (accentuating its vitreous ‘glassy’ luster), and an attractive overall appearance (outline, profile, proportions, and shape). Optimal lapidary also minimizes the aesthetic impact of color unevenness due to zoning (location of color in the crystal versus how the gem is faceted), or excessive windowing (areas of washed out color in a table-up gem, often due to a shallow pavilion), both important value considerations. While ovals are the most common Sapphire shape, Madagascan Pink Sapphires are also available in pears and rounds.

While both Ruby and Sapphires are classified as Type II gemstones (gems that typically grow with some minor inclusions in nature that may be eye-visible) by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), Sapphires are usually cleaner (and larger) than Ruby, with an eye-clean clarity the marketplace norm. For Type II gemstones, ‘Eye-Clean’ is defined as no visible inclusions when the gemstone is examined six inches from the naked eye, minor inclusions at 10X.

Sapphires are also pleochroic (different colors visible from different viewing angles), but this is not usually a concern. As with all gemstones, assuming everything else to be equal, size matters for Sapphires, with one 4 carat Sapphire always far rarer (and more expensive), than four, 1 carat Sapphires.

Ruby and Sapphire are color varieties of the mineral Corundum (crystalline aluminum oxide), which derives its name from the Sanskrit word for Rubies and Sapphires, ‘kuruvinda’. Trace amounts of elements such as chromium, iron and titanium, as well as color centers, are responsible for producing Corundum’s rainbow of colors. While ‘Sapphire’ alone typically refers to its blues, its other hues are collectively described as ‘Fancy Sapphires’, with prefixes used to denote specific colors. Pink Sapphires are colored by chromium traces, the same element that makes Rubies’ red, with higher concentrations resulting in more intense colors. Ranging from pastel pinks to deep vivid pinks, sometimes with secondary oranges or purples, Pink Sapphires are differentiated from Rubies by saturation and tone. Pink Sapphire’s more intense colors are often identified by prefixes, such as ‘AAA’, ‘fuchsia’, ‘hot’ or ‘magenta’. While Pink Corundum is historically considered to be ‘Ruby’ in Asia, due to the immense popularity Pink Sapphire has garnered over the last 30 years, this term is now recognized globally. As red and pink are technically the same color, only varying in saturation and tone, and because Rubies are worth more than Pink Sapphires, arguments over where pink stops and red begins were once common. To resolve these disputes, in 1989 the International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA) sensibly stated: “Pink is really just light red. The ICA has passed a resolution that the light shades of the red hue should be included in the Ruby category since it was too difficult to legislate where red ended and pink began. In practice, pink shades are now known either as Pink Ruby or Pink Sapphire.” Sapphire’s name is derived from the Latin, ‘sapphirus’, which in turn comes from the Greek ‘sappheiros’, meaning blue stone. This name is believed by some to originate from either the Hebrew ‘sappir’ (precious stone) or the Sanskrit ‘sanipriya’. Used to describe a dark precious stone, ‘sanipriya’ means ‘sacred to Saturn’ and this etymology is lent credence by the fact that Sapphire is regarded as the gem of Saturn in Indian astrological beliefs. Historically, ‘sappheiros’ usually referred to Lapis Lazuli rather than Blue Corundum, with the modern Sapphire probably called ‘hyakinthos’ in ancient Greece. Believe it or not, Sri Lankan Sapphires were reportedly used by the Greeks and Romans from around 480 BC, which provides evidence of the ancient trade routes used by our ancestors. Like all famous gemstones, Sapphire features in mythological and religious stories. Whether these really referred to what we know as Lapis Lazuli or blue gems collectively during antiquity is uncertain. According to Greek mythology, the first person to wear September’s birthstone was Prometheus. While Persians believed Sapphire’s reflections gave the sky its colors, Sapphire is mentioned in the bible: Exodus (24:10), the throne of God is paved with Blue Sapphire of a heavenly clarity, it is also one of the 12 ‘stones of fire’ (Ezekiel 28:13-16) set in the breastplate of judgement (Exodus 28:15-30). As one of the 12 gemstones set in the foundations of the city walls of Jerusalem (Revelations 21:19), Sapphire is also associated with the Apostle St. Paul. Sapphires have long symbolized faithfulness, innocence, sincerity and truth, so it’s not surprising that for hundreds of years they were popular engagement ring gemstones. Apart from being one of the world’s favorite hues, blues are also psychologically linked to calmness, loyalty and sympathy. While Sapphire’s popularity as an engagement gemstone has been somewhat upstaged by Diamonds since the 50s, they’re making a comeback. For example, in 1981 Prince Charles gave Lady Diana an engagement ring set with a stunning 18 carat Ceylon Sapphire, and more recently (2011) Prince William tied the knot with Kate Middleton using the same engagement ring.

Rarity

Sapphires embody a gem’s quintessential ideals (breathtaking beauty, genuine rarity, and everyday durability), making it one of the world’s most coveted, enduring, and valued gemstones. Sapphire’s classic source, Ceylon (renamed Sri Lanka in 1972) holds the earliest record for Sapphire mining. While Sapphires traditionally hail from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and Myanmar (Burma, specifically Mogok), other sources include, Australia, Cambodia (Pailin), China, Ethiopia, India (Kashmir), Kenya, Laos, Madagascar, Malawi, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tanzania, Thailand, USA (Montana), and Vietnam.

Historically known as the ‘Beryl Island’ due to its abundance of gemstones and minerals, Madagascar has been a premiere Sapphire source since the early 90s, with most mining occurring at the gem fields of Antiermene, Diego Suarez, and Ilakaka. While Sapphires have significantly impacted the gem world’s perception of Madagascar, current activity is limited and sporadic, with the majority of Madagascan Pink Sapphires (raw crystals and cut) available in the marketplace old mining. Previously accounting for approximately 50 percent of the world’s Sapphires by volume (Source: GIA), Madagascar continues to be a very important and highly-regarded Sapphire origin, despite ever-decreasing marketplace availability. Madagascan Sapphires can even challenge those from renowned locales with an historic pedigree, such as Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Kashmir (India).

Revealed in 1998, Ilakaka’s widely dispersed alluvial gem gravels are one of the world’s largest Sapphire deposits, and are located close to route national seven approximately 130 kilometers northeast of Toliara (Tuléar, pronounced: too-LE-arr) in the Ihosy district of southwestern Madagascar’s Ihorombe region. With many new alluvial Sapphire discoveries unearthed around Ilakaka, as well as further southwest into the Sakaraha area, ‘Ilakaka’ now often not only refers to the main deposit, but also to the region’s entire gemstone mining area. There’s also a third location near Bezaha, close to the Onillahy River, 118 kilometers southwest of Ilakaka. Today, Sakaraha town is an international trading hub for the gems mined nearby.

Defined as any process other than cutting that improves a gems’ appearance, durability, value or availability, 90 percent of all gemstones in the marketplace have been enhanced in some manner. As these processes have become an important part of the modern gem industry, enhancements are acceptable as long as they are disclosed, permanent, and stable. While gemologists can often spot indications of gemstone enhancements, advanced scientific testing is frequently required for confirmation and absolute certainty.

Becoming malleable around 1900°C and melting at 2030°C, Sapphires can withstand incredible temperatures. Sapphires also have no cleavage (i.e. very high toughness), allowing them to endure high temperatures with an acceptable breakage risk. Heating Sapphires to improve clarity or develop color has been used in some form for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Likely practiced in the sub-continent over 4,000 years ago, heating is one of the earliest known gemstone enhancements. Early references to the heating of gemstones include Pliny the Elder in his ‘Naturalis Historia’, c. 77 AD and two Egyptian papyri dating to the 3rd or 4th century AD. The scientist Abu Rayhan al-Biruni not only developed the specific gravity scale, using it to identify many gemstones, but in his book, ‘The Book Most Compressive in Knowledge on Precious Stones’ (c. 1048 AD) he describes in detail the 1100°C heating of Corundum to remove dark colored areas. Interestingly, this is basically one of the same methods still used today. Referred to as ‘traditional’ or ‘standard’ heat, modern ‘low’ temperature enhancement involves heating Sapphires to 1200°C – 1700°C for anywhere up to an hour to 36 hours, often repeating the process to achieve the desired results.

While almost all Sapphires are heated, this is not always a simple ‘traditional’ process that originates in antiquity, with new techniques continuously being developed (e.g. heating with pressure, c. 2009). Often a sophisticated process that has taken experienced specialists’ decades to perfect, high temperature heating can significantly change a Sapphire’s original appearance (and value). For example, modern electric and gas furnaces can heat Sapphires to 1800°C (close to their melting point) for up to seven days, sometimes with this being repeated numerous times. These high temperatures allow the incorporation of additives, such as glass (filling cavities and cracks) and coloring agents (e.g. beryllium bulk diffusion to dramatically alter color). As these enhancements radically change the color and clarity of arguably inferior gemstones, Sapphires that have been heated with additives should be disclosed, and not simply described as ‘heated’.

Durability & Care

The world’s second hardest gemstone, Madagascan Pink Sapphire is an excellent choice for everyday jewelry (Mohs’ Hardness: 9). Madagascan Pink Sapphire should always be stored carefully to avoid scuffs and scratches. Clean with gentle soap and lukewarm water, scrubbing behind the gem with a very soft toothbrush as necessary. After cleaning, pat dry with a soft towel or chamois cloth.

Map Location

Click map to enlarge