From Cleopatra to conquistadors, the lust for its rare, beautiful greens has made Emeralds one of the world’s most valuable gemstones. Twenty times scarcer than Diamonds, May’s birthstone remains exceedingly rare. Discovered in 1928, Zambia’s fine quality’s prized due to their vivid ‘classic emerald-greens’ with blue splashes conveying richness, wonderful brilliance, and clarities typically superior to Colombian! These exceptional Emeralds are from the acclaimed Kagem Mine located in Zambia’s famous Copperbelt Province. Optimally cut and vaulted in Jaipur, they were secured through close, trusted personal relationships, maintaining excellent market-value.

Beauty

Color is king for Emerald with four criteria determining beauty and value:

1. Color Purity

2. Transparency

3. Clarity

4. Brightness (signature Emerald brilliance, often described as glowing, satiny, silky, soft, or warm)

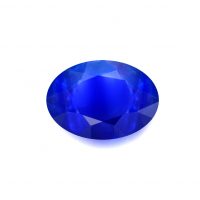

A celebrated gemstone from an acclaimed 20th century locale, Zambian Emerald displays slightly bluish-greens (pure green with a hint of blue bringing depth and warmth), in a highly-desirable medium saturation (strength of color) and tone (lightness or darkness of color), with excellent clarity and transparency, affording its characteristically beautiful ‘green fire’ brightness.

As a GIA (Gemological Institute of America) Clarity Type III gemstone (typically grow with many inclusions in nature that are usually eye-visible), Emerald’s visible inclusions, termed ‘jardin’ (French for ‘garden’), are a characteristic trait and totally acceptable. Emeralds usually grow slowly within metamorphic rocks (rocks that have undergone a physical change due to extreme heat or pressure), which limits their size. This violent environment, combined with chromium and vanadium trace elements, encourages the formations of inclusions. All things being equal, cleaner larger Emeralds are worth more simply because of geological scarcity. Our Zambian Emeralds are only slightly-included, an excellent clarity for Emerald. ‘Slightly Included’ for Type III gemstones are minor inclusions visible to the unaided eye with moderate 10X inclusions.

Optimal lapidary is critical for Emeralds, as a skilled cutter can locate its inherent inclusions in a way that minimizes their beauty impact. Zambian Emerald also displays medium to strong dichroism (two different colors visible from two different angles, yellowish-green and bluish-green), making crystal orientation during lapidary critical. These Zambian Emeralds were expertly faceted in the legendary Indian gemstone city of Jaipur, home to some of the world’s best Emerald lapidaries, maintaining careful orientation to maximize their colorful beauty and signature brightness, with a high/mirror-like polish accentuating its vitreous ‘glassy’ luster, and an attractive overall appearance (outline, profile, proportions, and shape).

The famous equidistant steps of the ‘emerald cut’ are designed to reduce cutting pressure, accentuate Emerald’s satiny brightness, and in the case of Colombian Emerald, maximize crystal yield. While this traditional cut is synonymous with Emerald, cushions, ovals and pears are also possible for Zambian Emeralds. Crystals not suitable for faceting are often fashioned into cabochons and beads.

Emerald’s name is derived from the Greek ‘smaragdos’, which means ‘green gem’, via the French ‘esmeraude’, but as with Ruby and Sapphire for reds and blues, prior to scientific advances in the 18th century, the name was used for any green gemstone. For example, Green Sapphire from the Far East was once known as ‘Oriental Emerald’, and many of Cleopatra’s prized ‘Emeralds’ from Zabargad Island were actually Peridot. Emerald is a member of the Beryl mineral family (from the ancient Greek ‘beryllos’, meaning blue-green stone), commonly known as the ‘mother of gemstones’, due to its highly-regarded gem varieties. Pure Beryl is colorless and trace amounts of elements are responsible for producing Beryl’s wonderful colors. Apart from Emerald’s greens, other Beryl gemstones include, Aquamarine blues, Golden Beryl yellows, Goshenite whites (colorless), Heliodor greenish-yellows, Morganite pinks, and Red Beryl reds. Emerald is colored by trace amounts of chromium, vanadium and iron, with their relative concentrations causing an extraordinarily beautiful range of pastel to intense deep greens, with varying degrees of bluish, brownish, greyish, and yellowish tints. Some professionals and gemological laboratories split Green Beryl and Emerald based on their coloring agents, color purities, hues or tones. In her excellent book, ‘Ruby, Sapphire & Emerald Buying Guide’, Renée Newman states: “there is no agreed-upon criteria in the trade for distinguishing between Green Beryl and Emerald”. She favors keeping it simple for consumers, using ‘Emerald’ to refer “to all Beryl ranging from bluish green to yellowish green regardless of its tone, color purity or coloring agent”. While an ostensibly sensible approach, there is typically a strict tone description required for Emerald. If it is not medium or darker many do not consider the gem Emerald. Instead they classify it as ‘Green Beryl’. While this might seem reasonable for practical purposes, scientifically the variety is defined by its coloring agent. The American Gemological Laboratory New York (AGL) recognizes any Green Beryl colored by chromium and/or vanadium as Emerald regardless of tone. Almost all Emeralds contain iron as a trace element, though the amount may change from one formation to another. A Beryl variety that owes its green color to iron only is typically named Green Beryl. Prized for millennia, Emeralds are truly ancient gemstones, reportedly first traded 4,000 years ago. Historically, Emerald was the mean green beauty machine of the ancient world; Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks and Romans all coveted the ‘greenest of green’ gems. For early civilizations surrounding the Mediterranean, Egypt is the place where Emerald’s story begins. Perhaps mined as early as 3500 BC, Egypt’s Emerald mines were located in Egypt’s eastern desert region and were rediscovered in 1816 by Frédéric Cailliaud, a French mineralogist and explorer. Even Greek miners braved heat, scorpions and snakes to unearth Emeralds there for Alexander the Great. This isn’t to say there weren’t other Emerald sources; the Habachtal region in the Austrian state of Salzburg might have yielded a few Emeralds, and Roman earrings featuring Emeralds from the Mingora mine in Pakistan’s Swat Valley have been discovered. There is also a legend that the Scythian Emeralds mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Historia Naturalis were actually from Russia’s Urals, but as far as supply is concerned, Egypt had a near monopoly. Cleopatra, last Pharaoh of Egypt, was big on Emeralds; she wore sumptuous Emerald jewelry, decorated ornamental objects with them, and presented dignitaries with Emeralds carved with her likeness. While it’s tempting to think they were her favorite simply because of their beauty, Cleopatra was shrewd, intelligent and politically savvy. She understood the importance of symbolism, glamor and prestige in power and politics. Emeralds were more than just pretty gems to the Egyptians; they were potent patriotic symbols of national pride and she knew this. When Cleopatra finally consolidated her power base in 47 BC, with a little help from her Roman boyfriend Caesar, she was quick to claim the country’s mineralogical riches as her own. Despite being discovered some 2,000 years before her birth, the Egyptian deposits will be forever known as ‘Cleopatra’s Emerald Mines’. Taken over by the Romans after her death, Egypt’s Emerald mines were worked until the 6th century AD. Featured in myths and legends in diverse cultures around the globe, Hermes gifted Aphrodite an enormous Emerald in Greek mythology, while in Hebrew tradition Emerald was one of the four precious stones given to Solomon. The ancient Romans associated Emeralds with fertility and rebirth, dedicating it to Venus, their goddess of love and beauty. One legend recalls Satan losing an Emerald from his crown when he fell, which was then apparently shaped into a bowl, and sent to Nicodemus by the Queen of Sheba. According to this story, Christ then used the bowl at the last supper, with Joseph of Arimathea using it to catch blood from Christ’s crucifixion, founding the order of the Holy Grail. Since Egyptian times, Emeralds have been linked to fertility, immortality, rejuvenation, and eternal spring, so it’s no surprise they are the birthstone for May. Pliny bestowed the benefits of Emeralds to refresh and sooth strained eyes, stating “nothing green is greener”, also recording Roman Emperor Nero wearing Emerald spectacles while presiding over gladiatorial fights. Even today, we have ‘green rooms’ to relax presenters in TV studios, and ‘hospital green’ to calm patients. Regarding Nero’s ‘Emerald’ glasses… gemologists today regard this highly unlikely, as the ancient Egyptian Emerald mines yielded crystals of insufficient size and clarity needed for such an instrument, with historians now speculating Aquamarine or Green Beryl were more likely used.

Rarity

One of the ‘big four’ gems (Emerald, Diamond, Ruby & Sapphire), and Beryl’s most prized gemstone variety, Emeralds remain very scarce. Emerald sources include, Australia, Afghanistan, Brazil, Colombia, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Russia (Ural Mountains), Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Since the 16th century exploits of the infamous conquistadors Hernando Cortés (who campaigned against the Aztecs from 1519) and Francisco Pizarro (who campaigned against the Incas from 1526), a Colombian pedigree has become synonymous with Emeralds of exceptional quality. Unsurprising considering Colombia enjoys the world’s largest and most substantial Emerald deposits. While Brazil’s the biggest Emerald miner by weight, measured in value, Colombia remains largest, followed by Zambia, Brazil, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Russia.

Zambia is situated in a mineral rich region, surrounded by neighboring countries famed for their gemstones, including Mozambique and Tanzania. The world’s second largest Emerald deposit was discovered in the Kafubu District in north-central Zambia’s famous Copperbelt Province, about 45 kilometers southwest of Kitwe, in 1928 by Dick and Baker. Geologists from the Rhodesian Congo Border Concession Company, they reported their investigation in 1931, with this often incorrectly cited as Zambian Emerald’s year of discovery. In 2005, a small Emerald deposit (Musakashi Mine) was unearthed at the Mushindamo District in Zambia’s North-Western Province, featuring an intense bluish-green color, similar to Emeralds from Muzo, Colombia. Zambian Emerald was created by billion-year-old metamorphic rock encountering million-year-old granite, mineralizing from the interaction between metabasites (metamorphosed igneous rock) and granite pegmatites (coarsely crystalline igneous rock) and their associated hydrothermal fluids (low-viscosity, heated by Earth’s interior energy, typically containing volatile components including, carbon, chloride salts, sulfur, and water). Emeralds are found between the talc-magnetite schist (coarse-grained metamorphic rock), providing Emerald’s essential coloring agent chromium, and pegmatites, the beryllium mineral source, as well as in Quartz-Tourmaline veins, which only yield miniscule amounts of fine gemmy Emeralds. Large scale Emerald mining began in Zambia around 1976, with Tiffany & Co. first promoting Zambian Emeralds in 1989. While Colombia remains the largest miner, Zambia’s very significant, contributing approximately 20 percent of the world’s Emeralds, a substantial portion of the global market. Today, Zambian Emeralds distinctively beautiful characteristics are highly-regarded and well-respected.

Known for their fine quality, Zambian Emeralds have captured jewelry connoisseurs’ hearts around the globe, due to their deep, rich, vivid hues, from the presence of iron (along with chromium and vanadium), and comparatively, fewer inclusions. Typically possessing a better clarity than Colombian Emeralds, Zambian Emeralds are also usually more transparent, possessing an even color with no zoning, and excellent brilliance due to a refractive index higher than most other important Emerald deposits. Typically ranging from green to bluish-green, Zambian Emeralds are usually slightly darker and more saturated than Colombian Emeralds. However, some Zambian Emeralds are much lighter, with more yellow undertones, especially under incandescent candlelight. Fine Zambian Emeralds have an almost clear, ‘pure’ green, placing them near the marketplace quality pinnacle, even occasionally, arguably rivalling the color of Colombian Emeralds.

Our Zambian Emeralds are from the Kagem Emerald Mine, covering approximately 46 square-kilometers within a 200 square-kilometer mining zone, in the Kafubu Emerald Mining District. Founded in 1984 to regain control of the district’s mines, Kagem is reportedly Africa’s largest Emerald mine, unearthing approximately 50 percent of Zambia’s Emeralds since 2010, around 10 percent of the world’s demand. For example, Kagem unearthed 37.2 million carats of Emeralds and Beryl, including 259,500 carats of premium Emeralds in 2022. While experimenting with underground operations, Kagem is primarily an open-pit mine, affording access to every carat of Emerald. Currently operating the Chama open pit, as well as the bulk sampling pits at Libwente and Fibolelem, miners use hammers and chisels to recover the Emeralds once the surrounding rock is removed. Core drilling to 2,500 meters at Chama, the pit’s around 1,000 meters by 600 meters, reaching 120 meters deep. In 2008, the British public-listed Gemfields Resources PLC acquired 75 percent ownership of the mine from the Zambian Government. Socially responsible, Kagem works with local communities to actively evaluate environmental and social issues, improving deficiencies through dedicated programs. In 2014, the mine was reported to be viable for another 25 years. There are also other mechanized mines, as well as many artisanal miners, working the Kafubu Emerald Mining District.

Regardless of origin, at least 99 percent of all cut Emeralds are sold with some sort of clarity enhancement, for example natural colorless cedarwood oil or colorless liquid polymer resin fillers. As Emeralds are never found with naturally occurring oils or resins, all Emerald clarity enhancements are considered artificial processes, and are universally accepted in the trade with proper disclosure. Stable minor clarity enhancement with colorless fillers are generally preferred, over moderate or heavy filling, and/or colored fillers. For further information on this important gem industry subject, please see the International Gem Society online article.

Sources: ‘A Visit to the Kagem Open-pit Emerald Mine in Zambia’, by Tao Hsu, Andrew Lucas, Vincent Pardieu, and Robert Gessner, 31st December 2014, Gemological Institute of America; and ‘Update on Emeralds from Kagem Mine, Kafubu Area, Zambia’ by Ran Gao, Quanli Chen, Yan Li and Huizhen Huang, Minerals 2023, 13 (10).

Durability & Care

Zambian Emerald (Mohs’ Hardness: 7.5 – 8) is an excellent choice for everyday jewelry. Always store Zambian Emerald carefully to avoid scuffs and scratches. Clean with gentle soap and lukewarm water, scrubbing behind the gem with a very soft toothbrush as necessary. After cleaning, pat dry with a soft towel or chamois cloth.

Map Location

Click map to enlarge